Valéria Gašparová home page

Building a State: Art, Architecture, Design and National Identity

The National Gallery in Prague, Trade Fair Palace, Dukelských hrdinů 47, 170 00 Prague

Opening: 20.11.2015 | 17: 00 CET

20.11.2015- 7.2.2016

Team: Cyril Říha, Petr Klíma, Jakub Potůček, Vojtěch Marc, Valéria Gašparová

Source: Archive TASR

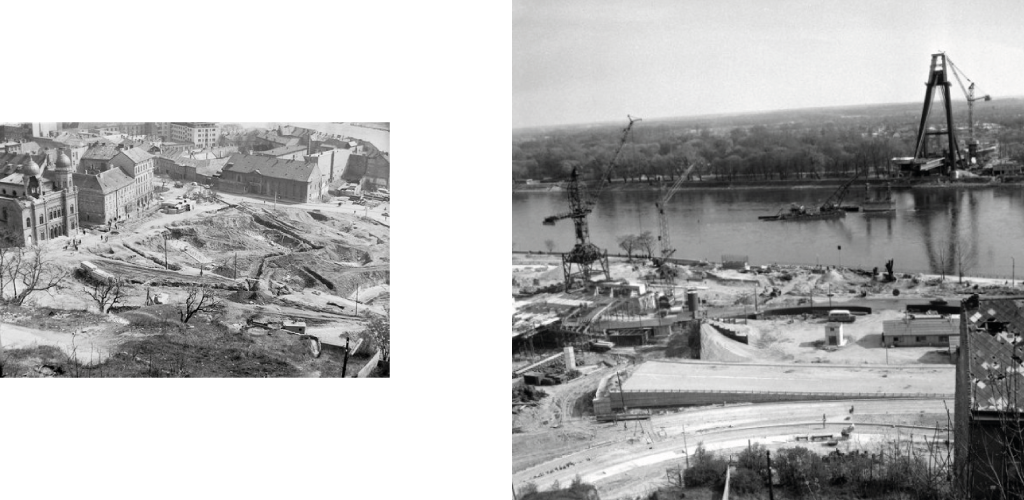

The Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising or the Demolition of the Historic Quarter of Podhradie

An example of another exceptional building project linked to the massive demolition of the historic city, is the unique construction design of the Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising in Bratislava. With main span of 303m, the bridge was the subject of admiration even during its construction, and in 1969 was among the most impressive cable-stayed

bridge is 431,8m long 21m wide and its height from the ground reaches 95m. The Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising was designed by architects J.Lacko, L.Kušnír and I. Slameň and engineers A. Tesár and J. Zvara. In 1967-1972, the bridge was built by the state companies Doprastav, n.p, Bratislava, and Vítkovice, n.p, Ostrava. The bridge reflects the rapid population growth in Bratislava during the period and the related matter of the newly planned construction of a housing estate in Petržalka, i.e. in the region that had been previously populated with Germans and Hungarians on the right bank of the Danube. It also reflects the gradual demolition of the left bank of the Danube that took place, primarily in the Jewish quarter of Podhradie, starting in 1948.

A design for two typologically distinct bridges, that would span the Danube was proposed in 1960s.The first was a highway bridge, originally planned for the periphery, and the second was a bridge for intra-city transportation with a promenade that was to connect Petržalka with Bratislava’s historic center. The plan for two bridges was not approved, which is why the original concept of the bridge with a colonnade was changed into a highway bridge with an arterial road leading into the very center of Bratislava. The change in the scale of the bridge shattered the original compact form of the old town and required the demolition of additional buildings. However, the intervention into the city’s physical structure only followed a radical change in its social and ethnic stratification, from which first the Jewish and then the German community vanished after the Second World War.

There still exists a polarity of views on the urban context of the bridge as well as on the form of the work itself. The connection of the old and new part of the city had already failed when the old part irretrievably disappeared. The city still had not absorbed this massive intervention in the form of a highway intersection of the urban structure at its most exposed part.

Text: Valéria Gašparová

Photo:TASR/Viliam Přibil

Bibliography

Juraj Bončo – Ján Čomaj (eds.), Búranie Podhradia, Stavba Mosta SNP, Bratislava 2010.

Wai-Fah Chen – Lian Duan (eds.),Handbook of International Bridge Engineering, Lodon – New York 2014.

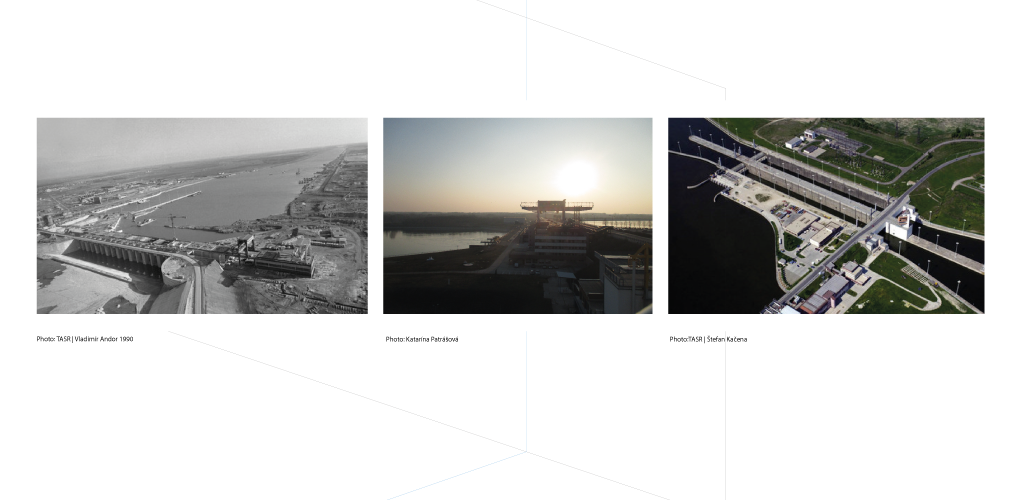

Gabčíkovo Dams or a Symbol of State Construction

One of the main reasons for the construction of waterworks is the use of water as an energy resource for economic purposes. Moreover, “the support of large dams

often becomes a symbol for state building and national pride and in many cases they are meant to contribute to national unity. “1 In the period when the Soviet Union championed plans for large dams systems aimed at accelerating national develoment, one of the projects drawn up was an extensive plan for the shared used of the Czechoslovak-Hungarian section of the Danube for the construction of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros dams. One of the project’s main objectives was to provide flood control and improve river navigation conditions on the section between Bratislava and Budapest. Both involved countries also expected that jointly produced electricity would improve their respective power supply.

After the agreement was signed between Czechoslovakia and Hungary in 1977, implementation of the project could begin. The construction of waterworks on the territory of the former Czechoslovakia required that the Danube be diverted from the original river bad to a manmade canal. Only then could the Gabčíkovo dams with 158 MW of power was to be built on the Hungarian side near the city of Nagymaros. It was planned, above all, for the need of the water’s level control. In the early 1980s, Hungary requested that the projects be stopped due to financial reasons, and concurrently intensifying protests initiated by both experts and public alike led to the Hungarian government’s decision to abandon the project in 1989. At this point, however the construction work on the Czechoslovak side was nearly done and, due to this crisis, the Czechoslovak government agreed to an alternative solution. The implementation of this variation was accompanied by the diversion of the Danube towards the newly built canal in Čuňovo and the effects of a record drop in the river’s level set off a considerable international conflict.

The created 46km2 reservoir of the Gabčíkovo dams represents only a fragment of the originally intended plan that was borne by an ideologically oriented vision of the national development and cooperation.. This failure occured at the same time that the entire political system began to collapse.

Text: Valéria Gašparová

Notes

1.Cecilia Tortajada – Dogan Altibilek – Asit K.Biwas (eds.), Impacts of Large Dams: A Global Assessment, Berlin Heidelberg 2012, p.3.

The project was realized by the Department of Art History at the AAAD and implemented as a part of NAKI Program of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.